The coming battle over banking in the metaverse

On January 18, Microsoft announced the biggest acquisition in its history. The all-cash offer for Activision Blizzard values the game publisher behind Call of Duty, Warcraft and Candy Crush at $68.7 billion.

That’s far ahead of the $26 billion Microsoft paid for LinkedIn in 2016 or the $8.5 billion it paid for Skype back in 2011.

Three billion people now play games online. Microsoft expects that to reach 4.5 billion by 2030. Satya Nadella, chairman and chief executive of Microsoft, talked enthusiastically on the analyst call about gaming as the fastest-growing category in entertainment and one that, during the Covid lockdowns, helped people “maintain a sense of community and belonging, even when they’re apart”.

But the deal is about more than capturing growth in the number of gamers and extracting subscription revenues from them.

Gaming simply points the way for all manner of other online activities to be based increasingly on augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR).

Money is flowing into metaverse plays, note Jon Gordon and Sundeep Gantori, strategists at UBS.

“While we think the metaverse itself remains more conceptual than fait accompli at this stage," they say, "it is also clear that neither investors nor companies are waiting on the sidelines.”

Bobby Kotick, Activision BlizzardThe big bet Microsoft is placing here is on the growth of the metaverse, or rather of metaverses, a much-used but ill-defined term for online communities in which people immerse themselves thanks to VR technology.

They aren’t just playing games. They are completing tasks, earning, buying and selling.

Bobby Kotick, chief executive of Activision Blizzard, explains the incentive for accepting Microsoft’s bid: “Connecting these communities together is the next step in the creation of the metaverse. The race to do this is accelerating, and the resources required for success are enormous.”

Nadella lays out the vision of a “river of entertainment” in which “the content and commerce flow freely”. It’s the commerce part that financial services incumbents should be thinking about. There’s an opportunity here, though it may be a difficult one to grasp.

Nadella says: “We believe there won’t be a single, centralized metaverse – and there shouldn’t be. We need to support many metaverse platforms, as well as a robust ecosystem of content, commerce and applications.”

There will be – indeed, there already are – banks in the metaverse. People are spending real money – and lots of it – in it, and money could equally flow the other way.

Working 3.0

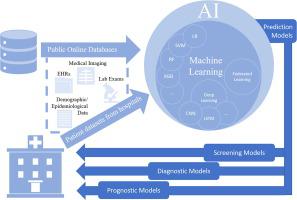

Several powerful technology streams now crossing each other promise the next stage in the transformation of digital finance. Incumbent banks are already being disrupted by blockchain technology, crypto assets, decentralized finance protocols and exchanges run by distributed autonomous organizations rather than traditional corporations. They are spending heavily to stay on top of all of that.

Now comes a new challenge.

Metaverses are a part of what is being called Web 3.0. This comes after the now familiar web 2.0 phase, which itself followed the earlier, static web 1.0 internet of consumers looking at company and media home pages.

Web 2.0 has brought us to today’s mobile internet delivered on smartphones, powered in the cloud rather than on local servers and characterized by large-scale platforms – for shopping, chat, broadcasting, ride-hailing and food-delivery – as well as by subscriptions to streaming media.

Satya Nadella, MicrosoftA growing proportion of commerce, and increasingly of banking, is conducted on web 2.0 through application programming interfaces (APIs).

Users of these web 2.0 services did not realise that they themselves were the product and that data on their usage and their identities was being sold to advertisers by the dominant platforms. Companies such as Facebook and Alphabet, the owner of Google, are the kings of the 2.0 world and the rest of us, the users, merely their serfs.

Web 3.0 at least holds out the promise of a more decentralized internet, with creators keeping more of the economics and users retaining privacy or at least the right to withhold or to sell their own data. Data, the new thinking goes, is as valuable as money – is in fact, a form of money – and should have the same protections.

Its promoters claim web 3.0 has the chance to be more democratic, although cynics might suggest some of those promoters see a chance to be the new monarchs there.

It’s still not clear, for example, what the key hardware will be to access the metaverses and whether a new company or companies can benefit in the same way Apple did from the extraordinary sales of the iPhone.

On January 3, 2022, Apple’s market capitalization briefly hit $3 trillion, the first company ever to reach that milestone. However, by January 20, as tech stocks sold off, it was down to $2.7 trillion

An even bigger question is how much of the growing digital economy, which the UN estimates accounted for 15.5% of global GDP in 2018 and Goldman Sachs estimates accounted for 16.8% of the world economy at the end of 2021 – will shift into immersive metaverses and AR.

Goldman technology analyst Eric Sheridan has tried to put numbers on this. He writes: “In the most bearish case with around 15% of the digital economy shifting towards the virtual world and around 2.5% market expansion from current estimated levels, we arrive at a roughly $2.6 trillion total market opportunity.”

What, Euromoney wonders, is the most bullish case?

Sheridan estimates that with “roughly 33% of the digital economy shifting to the metaverse and 25% market expansion, we arrive at a $12.5 trillion opportunity.”

These kinds of numbers make $68.7 billion seem like a modest amount to spaff up the virtual metaverse wall.

Goldman, of course, is advising Microsoft on the Activision deal, which still must pass likely reviews from competition authorities. Gaming is also consolidating, and this deal will make Microsoft the third largest gaming company in the world.

In some metaverses, friends and families will put on their goggles and pay to attend concerts by their favourite bands, while sitting on the couch at home. It will be a more advanced form of the kind of two-dimensional concert streaming onto laptops and televisions that emerged in lockdowns.

It will feel at least a little more like actually being there and less like watching a screen, which is, in truth, no way at all to experience the communal thrill of live music.

Working in the metaverse's favour is the fact that it still remains to be seen how restricted and risky travel will be if new Covid mutations spread.

Humans like to explore and have adventures. Could many more people engage in tourism and risky adventure sports through AR, visiting far-flung locations, parachuting or heli-skiing from their homes?

Time will tell if the technology becomes good enough.

In more prosaic metaverses, real-estate brokers will take renters and buyers on virtual tours of residential and commercial property. To do so, they will have to buy their own virtual space in the go-to metaverse for such business, just as auction houses are already buying virtual space from which to sell digital art.

In one of the first 3D virtual worlds, Decentraland, which opened to the public at the start of the Covid pandemic in February 2020 and is powered on the Ethereum blockchain, buyers have been paying with the platform’s Mana cryptocurrency for virtual plots of land. Ownership of these plots is designated by non-fungible tokens.

One Mana was worth about 40 cents in February 2020, and plots sold for the equivalent of about $20.

On January 20, 2022, one Mana was worth $2.86. It touched $5.48 in November 2021 after Facebook rebranded the company name to Meta. And parcels of virtual land have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Elsewhere, individuals will buy AR education and companies will pay for staff to be trained in all manner of skills: nurses, soldiers, pilots, perhaps even surgeons.

Spanning real and virtual

“The metaverse, just like the physical world, is going to be reliant on economic and commercial activity to fuel growth,” Brad Yasar, chief executive of EQIFI, tells Euromoney.

EQIFI is the first decentralized finance (DeFi) platform powered by a regulated bank.

Founded in 2018, EQIBank holds a full offshore banking licence in the Caribbean Community and is regulated by the Financial Services Unit of Dominica and the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank. It was set up to be a single bank in which customers could hold both crypto and traditional assets.

Now it is blazing a trail for banks into the metaverse.

It is already offering debit cards that span the real world and the virtual, and intends to open a fully fledged bank in the metaverse by partnering with Human Protocol, Polka City and Netvrk.

The genesis of EQIFI was to bridge the divide between established banking and DeFi, and to connect all the blockchains on which DeFi protocols operate. Now, Yasar says, “metaverses are being built on blockchains, and users will want ways to spend their 'metaverse dollars' in the real world, while at the same time using their fiat funds to purchase digital real estate and other collectibles in the metaverse.”

Those who immerse themselves in metaverses, many of which have native tokens like Decentraland’s Mana, can already do this. But it is very cumbersome.

Brad Yasar, EQIFIThey may have to sell the metaverse native token on a decentralized exchange, perhaps for the more recognized and liquid token of the blockchain on which it runs, such as Ethereum or Cardano. They must then exchange that crypto for a stablecoin, and finally exchange the stablecoin for fiat currency in a real-world bank.

“EQIFI is looking to establish a presence in each metaverse,” Yasar says. “That presence may be referred to as a branch or it might be a zone that you teleport to in order to access and transfer value. But we want to enable seamless transfers both between metaverses and between the virtual world and the real world, and to that end we’re speaking to a number of metaverses about the prospect of working together on a banking partnership.”

In the Polka City metaverse, EQIFI is offering debit cards based on NFTs that inhabitants can use to purchase items and services.

Users pay for assets such as plots of land in Polka City using the native POLC token and can also buy businesses such as virtual gas stations or shops, from which they can generate earnings in POLC.

EQIFI’s card now allows them to use other more liquid cryptos such as bitcoin and Ethereum to pay for things and fiat currency.

POLC is traded on the secondary market and EQIFI can track that value in dollars, euros or sterling, Yasar says. Customers with EQIFI and Polka City debit cards don’t have to only spend the value that they have created in the metaverse inside the virtual world. They can also get physical debit cards and drive to a gas station and fill up in the real world, converting value from POLC to fiat currency.

Euromoney pictures our children spending hours and hours in their goggles gaming merrily away and then not even wanting to take them off to order food via Deliveroo – though presumably they will have to before opening the front door when it arrives, as well as for eating it. But what do we know?

Polka City is a conventional two-dimensional metaverse accessed online from your mobile device or laptop in which EQIFI has a bank building and a couple of kiosks. The next step is to do the same thing in a fully immersive, 3D, AR metaverse. Some metaverses will also span the real and virtual worlds, for example connecting freelancers to job opportunities.

As more sophisticated metaverses emerge with their own economies, they will require more sophisticated financial services.

Plots of land are becoming more expensive in metaverses – where some early adopters hope to become virtual neighbours of their favourite real-world celebrities.

EQIFI intends to offer mortgages.

Again, these may cross the real and virtual worlds rather than being based purely on collateral values, earnings and debt service capacity within each metaverse and its native currency.

Yasar says: “We will allow people to take out loans against physical assets in the real world – as long as there is a market for those physical assets – and borrow to buy virtual assets.”

Regulators are looking hard now at crypto markets as they grow to prevent a spill-over risk for the regulated financial system.

Bitcoin crashed again in January, almost halving from its November 2021 high as, first, bond markets sold off and then equity markets corrected. But conventional banks still want to make money from the growing number of customers now buying, selling and investing in cryptos, while crypto-native exchanges and brokers seek licences to chase the same business.

“We want to show people that you can be regulated, licensed and compliant and still be in the metaverse offering new products to new customers,” says Yasar.

Evolving regulation

How banking that crosses between metaverses and the real world is going to be regulated remains an open question. Financial services became increasingly centralized, dominated by fewer and more systemically important banks in the years after the great financial crisis. Regulators found it easier to impose closer controls on fewer intermediaries in a more concentrated system.

What if web 3.0 accounts for a greater share of world economic activity and related financial flows but is also much more decentralized and less dependent on regulated intermediaries?

“Part of the distrust of big, centralized organizations so evident in younger generations is also a distrust of regulators,” one former regulator tells Euromoney. “One thing driving web 3.0 is that participants want to be in control of their own information. They don’t want to be the commodity.”

He adds: "This is all evolving so fast: cryptos, stablecoins, NFTs and the metaverse each have their own languages and their own regulatory issues.”

Some big crypto exchanges have decided there is no alternative but to engage with securities regulators. Stablecoins may even be subject to bank-like regulation rather than securities-like. NFTs seem to be a in a regulatory blind spot for now.

“As for the metaverse, that is very community-based,” the former regulator says. “In the end, these verticals will likely come together with full integration of DeFi into the metaverse. People will want to borrow against their NFTs. They may want to earn returns from lending those assets out. Someone will provide the liquidity for such borrowing and lending. It doesn’t have to be a bank.”

Will there be common global standards across the metaverses rather than today’s network of national banking jurisdictions in the real world? Will there be any standards at all?

There is time yet to grapple with all this. Web 2.0 developed and expanded over 20 years. Web 3.0 may take as long. We are now just scratching the surface of what the technology may permit.

“The potential might seem endless, but adoption will not necessarily be easy or happen overnight,” says Dani Brinker, head of investment portfolios at eToro, the social investing platform that is now offering retail investors a metaverse-themed portfolio of real-world stocks. “The metaverse will require larger processing capacity, bandwidth and improvements to hardware – headsets, glasses, smartphones and cloud services.”

It could yet be a damp squib. But Euromoney’s guess is that it’s going to be big and that it will potentially open to banks the chance to do all manner of business with possibly large numbers of new customers, including younger generations that the established banking system seems to be losing.

JPMorgan’s stock sold off after strong full-year 2021 results in mid January when it disclosed plans to invest $15 billion in 2022, some of that in marketing and distribution but the lion’s share in technology.

That’s the cost of staying relevant in the banking business.